AN EXTRAVAGANT NECESSITY…

On Madeira, British merchants had organized themselves into what they called the British Factory between 1658 and 1665. By 1812, the Factory had not only set up a fund to support the shipwrecked, the destitute, and other British subjects needing help, but also had created two cemeteries, a hospital, and owned fire engines. The Factory had been paying annual fees to several Portuguese officials including the island Governor and the salaries of the judge conservator and his scrivener, until the 1830s. The first evidence of their concerted effort to obtain a “place of worship” for British Protestant inhabitants on this island dates to 1808.

History teaches us that economics, often hand in hand with power, are the cause of certain cultural movements. For example, the Factory’s funding of a new military cemetery, also 1808, was ordered by the garrison commander General Beresford. One could easily draw the conclusion that the timing of a project to build a protestant chapel commencing at a time of British occupation of Madeira could hardly be a coincidence.

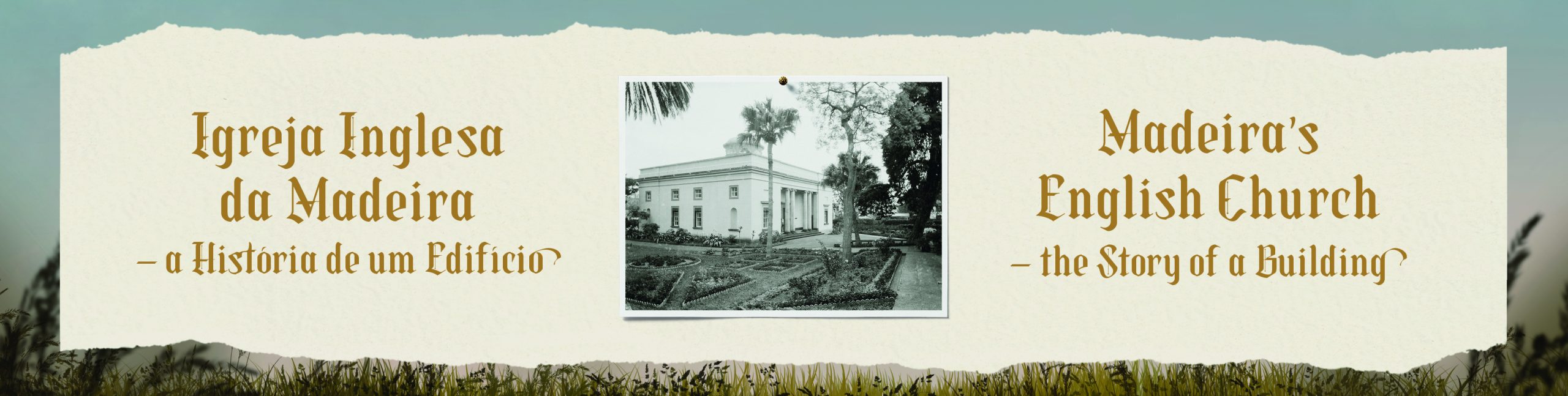

There is a record dating to 1810 in the British Factory books of a formal resolution that “each year the sum of two thousand mil réis” (about £400) be set aside from the Factory’s charitable trust for the building of a chapel. At the end of the same year, the British Factory purchased two suitable pieces of land, on which to build, at a cost of 4 400 000 réis, and an adjoining piece purchased some months later for a further 800 000 réis. These parcels form the area today in Rua do Quebra-Costas as the grounds of the English Church and its parsonage. Permission to build was sought (April) and obtained from King John VI by letter from Brazil (June) in 1813. The building of the chapel commenced in 1817 and was completed in 1822.

Plan of church buildings and gardens, 2015, HTC 375

A WATERY GRAVE NO LONGER…

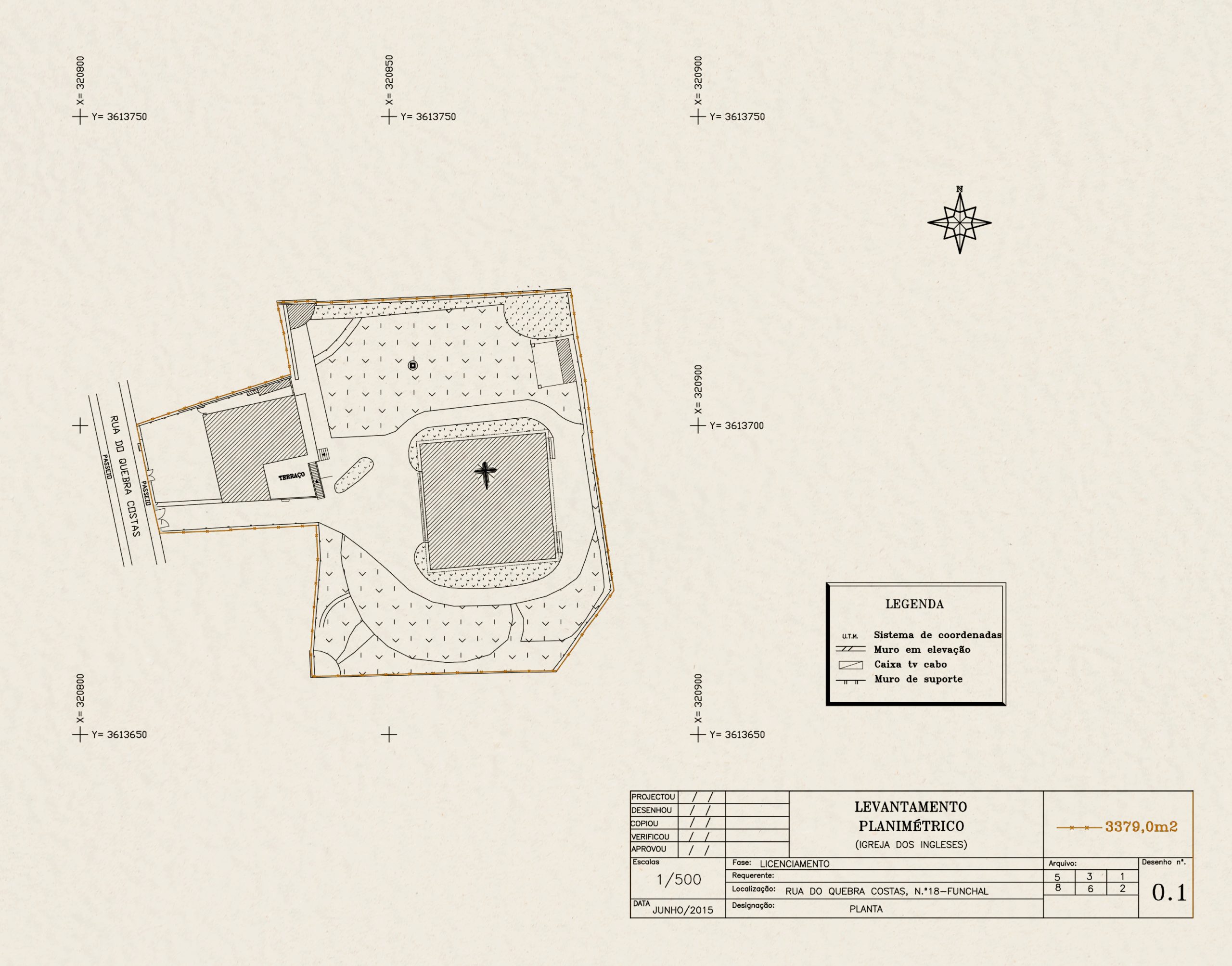

In 1654, following the execution of the English King Charles I, Oliver Cromwell, as Lord Protector, signed the Westminster Treaty with King John IV of Portugal. The treaty included allowing English residents in Portugal the right to practise their Protestant religion in private houses. However, it could be said that the history of the public practise of their religion began in 1761 when William Naish, the British Consul-General, obtained permission from King Joseph I to purchase a site for use as a graveyard, upon the condition it was outside the city. (Prior to this, declared Protestants had their bodies thrown off the cliffs into the sea near Garajau.) A site was purchased by the British residents just outside the perimeter of the city walls, fronting what is now the Largo do Visconde Ribeiro Real, at the western end of Rua da Carreira. It was called “The Nation’s Burial Ground”.

In 1887 Funchal city council ordered the compulsory purchase of this site for road development. It took three years for the members of the English church to relocate all the graves, memorials, and soil down to the bedrock, to the current British Cemetery, some 200 metres away. The original entrance gates to The Nation’s Burial Ground were then re-erected facing Rua Dr. Brito Câmara, where they can still be seen today.

The original entrance to “The Nation’s Burial Ground”, HTC 196

INITIAL CONCEPTS

Contrary to popular belief, Consul Henry Gordon Veitch did not himself design the building that was first known as the Factory Chapel, which became the Consular Chapel. (It acquired its full name of the Holy and Undivided Trinity when finally consecrated as a church in 1860 by the Anglican Bishop of Sierra Leone in whose diocese it was placed.) As a private chapel it had circumnavigated Portuguese laws preventing public Protestant worship. A clause forbidding a bell tower was included in the Royal permission.

We know from Consular Minutes that three designs were submitted from a source in London from which a sub-committee on 8th January 1817 made a choice. Consul Veitch was given the role of project manager. The chosen design we see today sits very much within the favoured British neo-classical religious vernacular architecture, which had started with church rebuilding following the Fire of London in 1666, but was in vogue as a go-to since 1760. At the end of its fashionable trajectory, here in Funchal it emerged in a simplified form, albeit with a possibly masonic-inspired sacred geometry. Contemporaneous financial church accounts records the name of the initial groundsman-engineer as João José dos Santos, and the subsequent architect of construction as Raphael Trajani, who was retained on a monthly salary of 45 000 réis.

British Consul Henry Gordon Veitch (1782-1857) and his wife Margaret, nèe Harrison (1786-1837), HTC 72

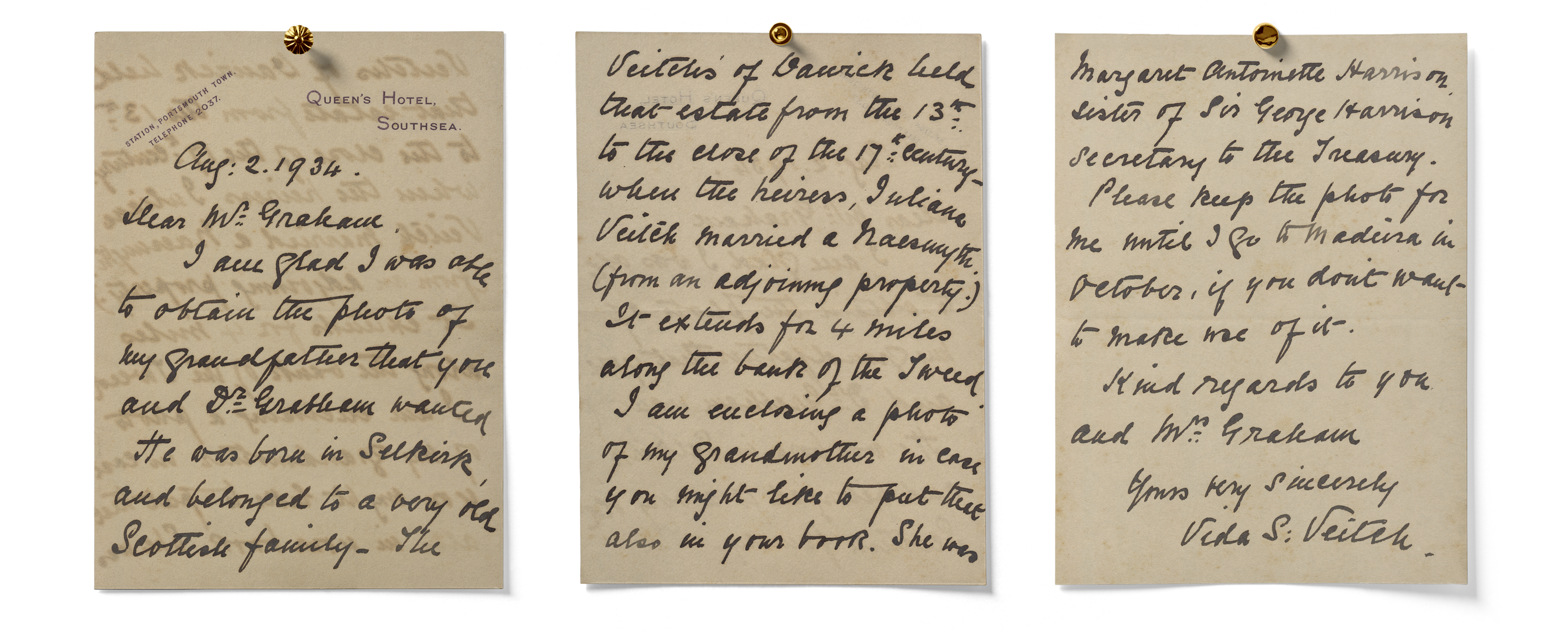

Letter from Vida S. Veitch to Rev. Graham, 1934-08-02, HTC 72

A baptismal font was commissioned from Lisbon in 1836 at a cost of 1 866 117 réis, from a design by local mason Francisco António da Silva for a fee of 3 000

réis. Its simple design (chosen from da Silva’s three options) includes, prominently, a triangle. Thus, although the church’s name was not official given until 1860 at its consecration, evidence suggests that the symbol of the Trinity/triangle was fixed from the chapel’s inception.

Interestingly, the building of the Anglican cathedral in Gibraltar post-dates that of the Consular Chapel in Funchal, but was consecrated first, and both share the name The Holy and Undivided Trinity.

FUNDING A CHURCH

In earlier narratives it was said the subscription list to fund the building of the chapel contained the names of George III, the Princess Royal, the Prince of Saxe Coburg (later King Leopold of Belgium), the Duke of Wellington, Lord Nelson, and the Duchess of Bedford, etc. However, recent research of prechapel financial records, now in the church archive, proves these were the names of ships contributing to the new Church Fund, and not the illustrious personages themselves. In fact, funding for the church building soon ran into difficulties with materials purchased in stages, and the original capital was raised via loans from individual merchants, repaid with interest annually from church funds. Each stone column with its capital cost 58 000 réis. This, together with problems with land drainage, accounts for the five years it took to complete the main structures. The interiors were unfinished when religious services began in 1822, with the pulpit installed in 1827 at a cost of 4 600 réis. The original decoration was simple and almost monastic with whitewashed interior walls in white and exterior in ochre.

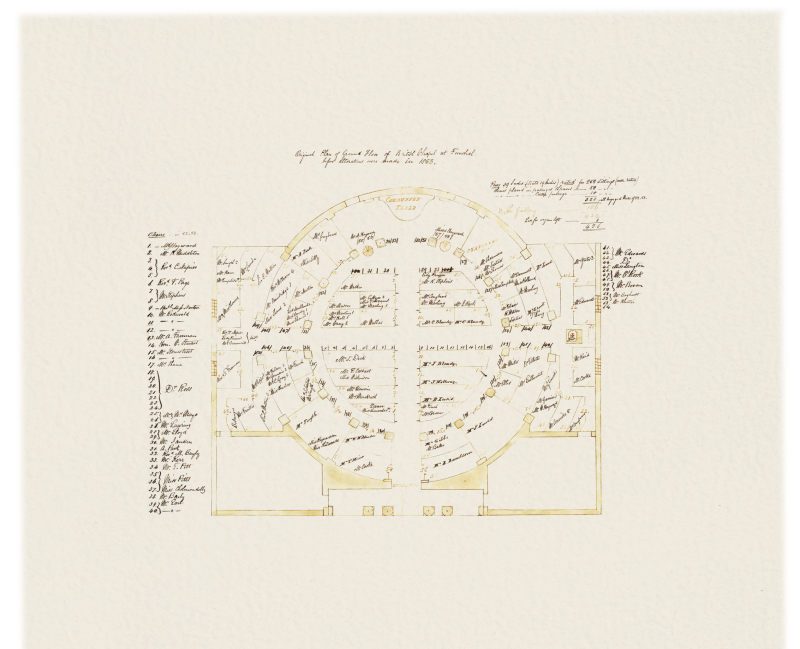

Floor plan showing original box pews, and family names, pre-1853, HTC 13

Contrary to appearances, the dome is a suspended wooden structure. In August 1830 the roof suffered damage as a result of the firing of cannons in the nearby Pico Fort. April, 1842 is the first registered attack by termites on the roof costing 500 réis to repair.

By 1837 records show that there were 368 seats contained within 36 box pews and 7 balcony boxes, with 12 temporary benches. Families paid an annual fee to reserve each box. The first chaplain’s salary was set at an ambitious £400 per annum, later attempts to reduce this proved tendentious.

A SACRED GEOMETRY

A thorough architectural survey was commissioned by the church council from the architect João da Cunha Paredes in 2015 in preparation for the Bicentenary. The project to create a concert hall in the crypt was abandoned due to lack of sufficient funds, but the restoration of the building commenced.

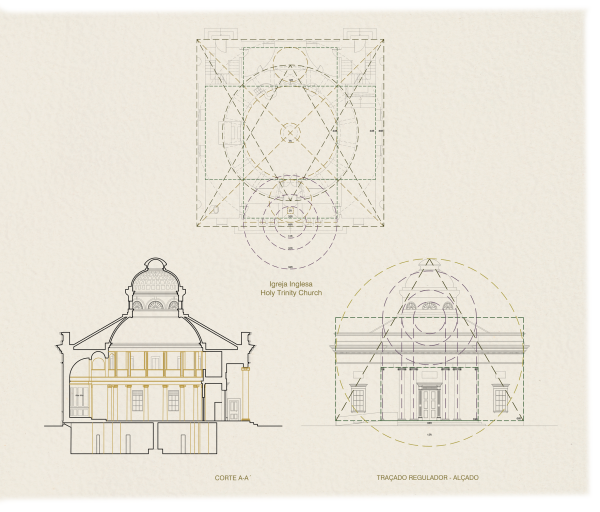

Moreover, the survey discovered the building’s sacred geometry, that employing imperial measurements, the chapel was constructed as a perfect square, each facade being 69 feet long, with multiples of the number 3 being used throughout its dimensions (the diameter of the circle of columns is 36 feet), and its interior design focused on the circle of columns: thus the descent of Spirit (circle) was manifest in the Material World (square). A point taken from the pinnacle of the dome, projected into each of the church corners produces a perfect pyramid.

Holy Trinity Church building architectural survey, 2017, HTC 375

Consul Veitch, forced to defend the chapel designs in the face of criticisms of a dissenting few, wrote that the inspiration was the Holy Sepulchre of Jerusalem

(interestingly the inspiration for both orthodox Christians and the Knights Templar). In October 1823 the church committee dismissed him as project manager, reverting to overseeing its management and furnishment themselves. Thereafter he continued to commission interior fittings from the United Kingdom without their permission, causing some animosity.

THE CHURCH INTERIOR DECORATION EXPLAINED

There were four main historical periods of decoration of the church interior: initial concept 1820-35, the Lowe years 1835-53, High Victoriana 1877-80, and Revisions of the 1930s.

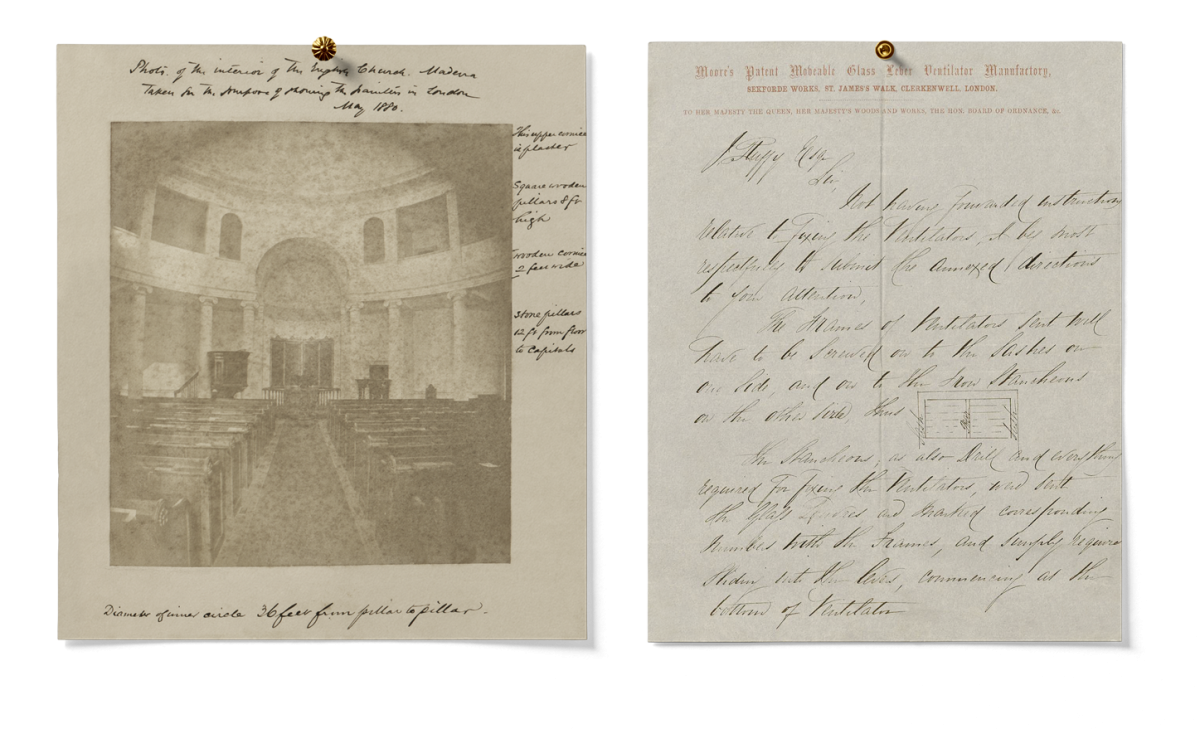

Church Interior (1853-1880), HTC 37

Original Design for louvre windows, 1853, HTC 25

The original box pews were finally removed in 1853 (funds had been provisionally agreed in 1836) and replaced with simple gothic bench pews, made locally to a description and materials sent from London, and which allowed for a larger congregation. Together with the baptismal font, and installation of the organ loft, such expensive changes suggest that the main thrust of the chaplaincy of Rev. Lowe was to move both physical and spiritual focus away from the circle and pulpit, and be refocused on the more rectilinear square and altar (communion table), in line with his Tractarian, Oxford Movement, theological leanings. The controversy these leanings provoked would escalate into a religious schism bursting the equanimity of Madeira’s Anglican community, reaching both the hallowed halls of Whitehall, Westminster and Windsor Castle, which echoed long after Lowe’s departure, and later death by drowning in the Bay of Biscay in 1874.

Little remains of the original interior decoration, apart from the dome’s Eye of God, and the building’s main structures. Even then, the interior walls separating what is today the north-west baptistry and south-west “welcome area” were long since removed to create a single interior space, the library and water closets they contained being moved to the new church hall and parsonage by 1930. The original pulpit and lay reading lecterns have both been lowered from their original height in several stages. The louvre windows are an original historic design (1853), and must have been an almost avant-garde solution at the time to facilitate air circulation.

The summer of 2022 saw the gothic pews finally removed and replaced with more adaptable, free standing, individual chairs as part of the Bicentenary renovations, creating a more flexible interior space.

A DREAM OF HIGH VICTORIANA…

The mid-19th century ring of slim, cast iron, palmette-headed pillars, seen under the balconies, and commissioned and shipped from the United Kingdom, were offered as a solution to the building’s instability, wrongly attributed at the time to a large increase in the size of the congregations in the 1850s, instead of the subsidence of the church’s north façade due to lack of an adequate foundation. A careful comparison of the north and south facades today will show that stone sill and lintel window embellishments were included in the 1858-60 rebuild of the north façade, matching the front and rear facades, but only painted simulations of such are found on the original southern façade.

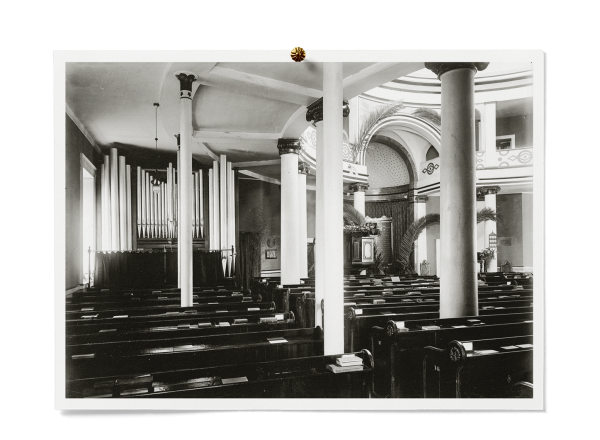

Interior (1880-1930), ground floor, PER 544

Church interior and Organ (1880-1930), PER 545

The main change to the interior decoration, that is still seen today, came in 1880, when De Wilde & Gardener, a firm of theatrical designers at 112 St. Martins Lane, Covent Garden, London, were invited to offer a fashionable redecoration scheme. The final scheme was a dramatic touch of High Victoriana that involved faux marbleizing of the stone columns with blackened capitols, hand-stenciling the balcony rail, adding an azure, star-spangled, ceiling to the apse, and painting the proscenium arch with a canvas-mounted mural with images of palm leaves and lilies, hinting at Pre-Raphaelite and Aesthetic Movements still in vogue. (Palm leaves and stone altars had been banned from church interiors since the iconoclast English Reformation.) The colour of the interior walls was described as Pompeian Red. After an onsite survey by the designer J. S. Gardener, eventually a lone craftsman was sent out from Liverpool on the SS Loanda with 5 cwt (250 kilos) of materials for the task, including turpentine and paint, and a £5 advance on his salary as a bribe, having mistaken Madeira for Botany Bay, as additional prompt to gird his loins! De Wilde himself refused to travel to oversee the work citing the precipitous geography and arduous experience of the sea journey. The unknown craftsman, armed with pencil sketches and colour notes for the designs for the apse and proscenium arch murals, cut the stencils for the balcony on site, to his own design, using as his reference “Florentine churches”.

REVISIONS IN THE 20TH CENTURY…

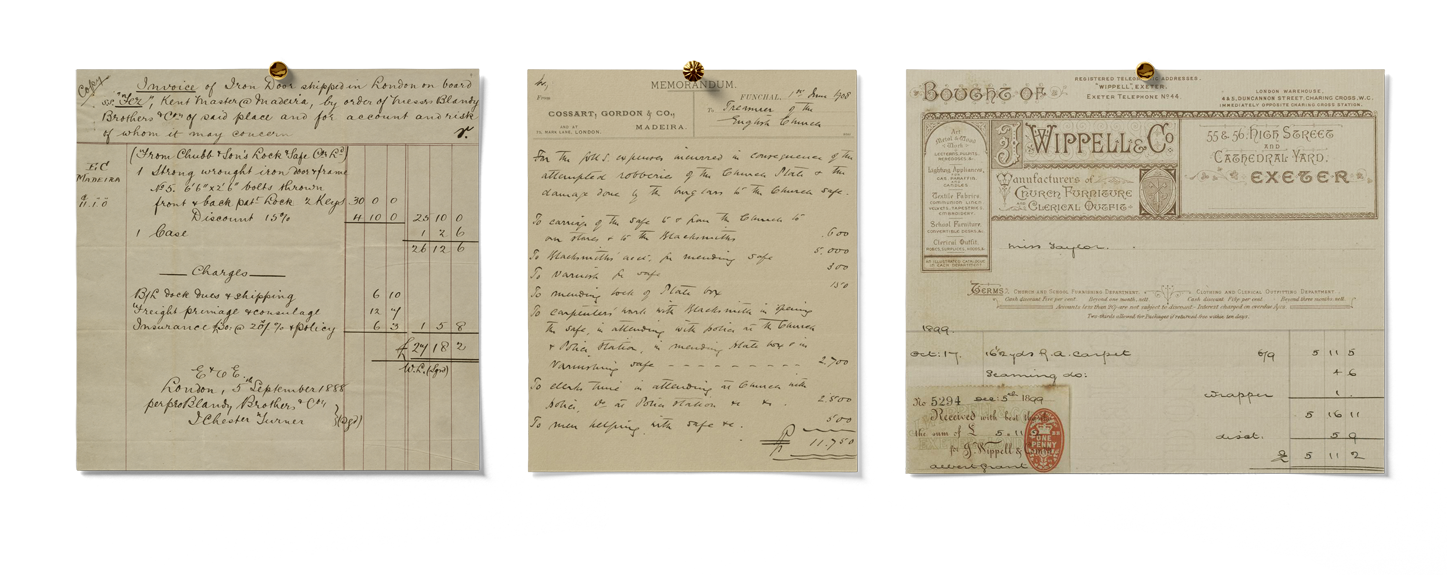

Records show that in 1908 the church suffered an attempted robbery of the church silver from its substantial strong room safe, which the church council had commissioned from Chubb & Sons, London, and installed in 1888. The safe door, though damaged, resisted and only money was stolen from collection boxes.

Copy invoice for an iron door safe commissioned to Chubb & Sons Lock Safe, London, 1888, HTC 89

Invoice for repairs to church and safe,

June 1908, HTC 25

Invoice from famous Exeter church suppliers

Wippell & Co, 1899, HTC 25

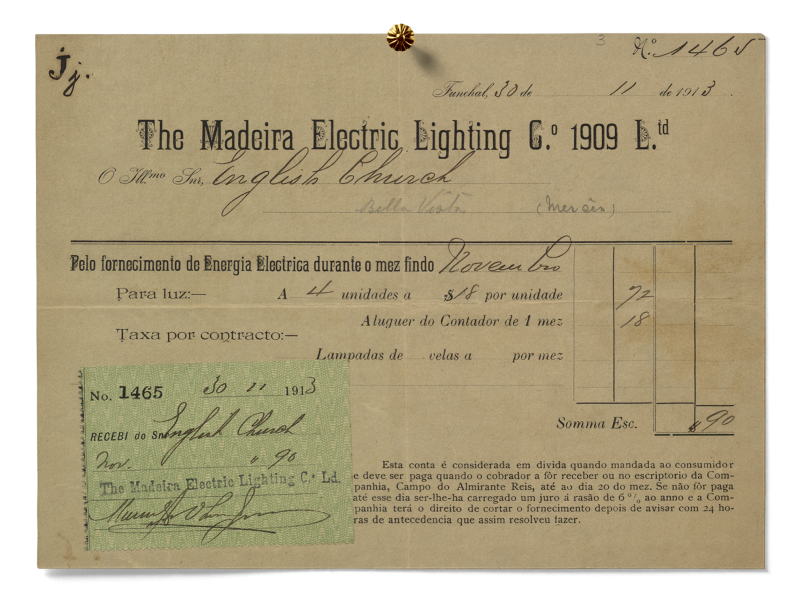

November 1913 saw electric lighting installed at a cost of 900 réis, but interestingly a meter was not installed until December 1914. (The Madeira Electric

Lighting Company Limited, the first electricity utility in Madeira, had opened in 1897.)

Invoice from Madeira Electric Lighting Co., for supply of church electricity, 1913, HTC 89

March 1915 saw a license granted to the church by Funchal city council for the erection of road signs giving directions to the “English Church”. Some of these may still be seen today, and it is still the description of the church most commonly known to the Madeiran People. The Lindon fund was used to build the chaplain’s house on land already owned fronting Rua do Quebra-Costas. Called The Parsonage, in 1925 the house was built by Messrs Leacock at the cost of £2300 plus an additional £680 for the church parish room.

In the 1930s, the church council decided that revisions were needed. The side chapel was created, furnished with a new carved oak reredos and communion table designed by Mademoiselle M. Brouhan and installed in 1937. The apse was furbished with impressive flame-mahogany panels and the original gilded tablets of the “Words of God” (which include the Apostles’ Creed, the Ten Commandments, and the Lord’s Prayer) which had hung as a centre piece behind the communion table since the chapel opened, were moved to the west wall where they remain today on either side of the main entrance. On a subsequent visit, the Bishop of Sierra Leone criticized the light colour of the side chapel oak furnishings and insisted they be darkened to match that of the new main apse communion table (altar) which had been designed in mahogany by the incumbent chaplain. The church council ignored his remarks until some years later, after Mademoiselle Brouhan had passed away. This is illustrative of how the church’s governing council over its history often chose its own path, often guided by its sensitivity to its own local congregation, and maintained a high degree of independence, which continues even today.

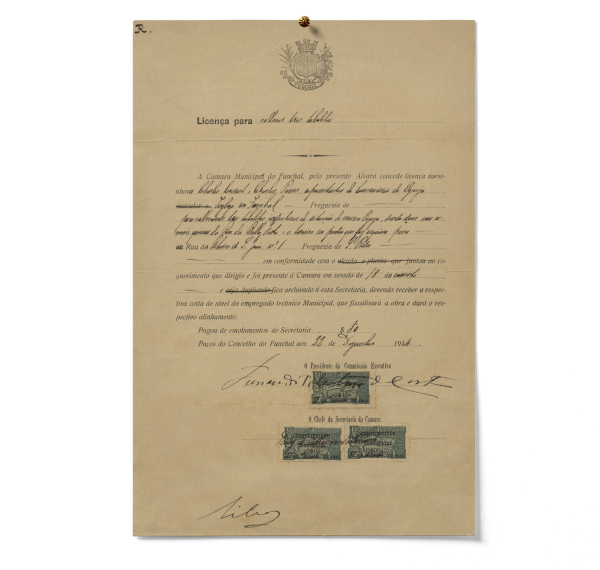

Funchal City Council certificate, for erection of church street signs, 1915, HTC 89